A Note:

The amount of mental anguish this silly little Russian has given me is… embarrassing.

Because as many have noted, to follow Mendeleev is to also follow the flow of Russian socioeconomics and politics in the 18th to early 19th century. I certainly ascribe to Michael Gordin’s interpretation of talking about Mendeleev as not only the man himself, but also as someone who experienced the Russian empire go from that of Tsars to one of huge uprising. Not only was the world rapidly changing politically, the world of science also underwent drastic changes.

I won’t claim to be a scholar, muchless one of Russian historical practice. Regardless, I am still deeply fascinated, as many are, by Mendeleev. Understandably so, he cuts a romantic figure. But as we know, there’s always more to the story.

Not to pour my heart out, but I’ve been challenged quite a bit lately. By myself, by society, by my circumstances. And I turned to my ol’ reliable – science history. Because I could lose myself in it for a good few hours, and because I think it’s important.

It’s hard work. Amateur internet sleuthing pays nothing but knowledge (and unexpected frustration with 40 year old Russian men, long dead, who just can’t seem to stop putting their fingers in all the pies.)

But it’s fun. I like this sort of stuff. I’m not complaining, merely communicating that this project, this post, and ultimately this website, are a promise to myself. In some sort of measure. That I’ll keep doing this. That I’ll keep writing.

So this is it. A few months of rebranding, re-writing, scrapping everything. Obsessing over what Russian University degrees were like in the 19th century, and caring way too much about oil tarriffs. But it’s here.

This is a living document. Edits will happen. Revisions will definitely occur. My goal is to have it all in one place and accurate. And that takes time. But I have to quit stopping myself before even starting the race. I have to put something out there. Even if it’s not perfect.

I have to absolutely honor my references, as always. This case is no different. I gained an incredible amount of insight and understanding from Michael D. Gordin’s book A Well Ordered Thing, which you can purchase here. I would not have a grain of understanding without this book, and I owe a lot to Gordin for his insight and analysis. This is my penultimate reference, but there are many to cite, and still many more to read. References and citations will comeabout more cohesively as the whole article is published.

So! Let’s dive in. We start in Siberia, in 1834.

Early Life and Education (1834 – 1859)

Leading a life that can only be described as profound, eclectic, and frustratingly complicated, Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev was born in a small village in Siberia outside of Tobolsk, Russia to Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleev and Maria Dmitriyevna Kornileva On February 8th, 1834.

Mendeleev is known for being the youngest of many children, but various sources report different numbers of siblings. It is generally accepted that Mendeleev had around 11 – 14 siblings; some reports state that Maria had given birth a total of 17 times but this is not officially corroborated, and it is believed that not all Mendeleev children lived to adulthood.

Mendeleevs’ mother, Maria, would prove to be the driving force behind her sons’ success. Maria, born of a once well-off merchant family trading in glass and paper, was denied formal education in her youth. Instead, she turned to her fathers’ vast library and took advantage of her brothers’ adjacent instruction. Education would prove to be very dear to Maria and eventually for her children.

An instructor at local gymnasiums (institutions then focused on primary and secondary education and preparation for university), Mendeleevs’ father, Ivan, suffered from poor health and lost his sight from cataracts around the time Dmitri was born. With her husband out of work, Maria resurrected an old glass factory that her family had abandoned years earlier.

It is said that Mendeleev regarded himself very much raised and a part of Asiatic Russian society, thousands of kilometers away from the bustling streets of Moscow and St. Petersburg. True, he was Siberian, but any speculation regarding any blood Asian inheritance stops there. He was simply a young man born to a middle class family that experienced Asiatic Russian influence and also Western European influence.

Tragedy struck thrice in Mendeleev’s childhood, initially uppercutting the family when their patriarch, Ivan, died in 1847. Shortly after in 1848, the now reborn glass factory (and primary source of income) burned down.

Faced with a crossroads, and with her youngest son soon approaching university age, Maria decided to take the more than 2,000 km trek to Moscow with Dmitri and his sister, Elizabeth, to enroll him at Moscow University. She was determined to get him a higher education, and hoped the connections that her brother, who lived in Moscow, would help Dmitri get in.

Upon arrival and application, however, Moscow University decided to reject Dmitri for schooling, even with Maria’s best hopes. Despite their efforts, the trio had to turn north, on to St. Petersburg.

There, the Main Pedagogical Institute (who had also educated his father, and is a part of St. Petersburg State University), accepted Dmitri as a student, but not without some of Ivan’s old friends pulling strings. Dmitri began his university education in 1850 at the age of 16.

Tragedy’s final blow came around this time as both Mendeleevs’ mother, Maria, and his sister Elizabeth fell ill and passed away. It is at this time that Mendeleev also fell into poor health. But still, he continued his studies.

Opting for a five year track with a later focus on natural history, Mendeleev graduated from the Pedagogical Institute in 1855.

He spent the next two years teaching in the Crimean Peninsula, first mistakenly assigned to Simerhof (which was at the time subjected to political upheaval), but eventually relocated to his original desire: Odessa.

Here he would teach and begin to research for his Masters’ dissertation focused on specific volumes. He would go on to successfully defend his research in 1856, and return to St. Petersburg in September of 1857, where he would stay to study and research interactions of alcohols with water for about two years.

In 1859 Mendeleev moved to Heidelberg, Germany to continue this work.

Heidelberg, Karlsruhe and the Beginnings of the Table (1859 – 1869)

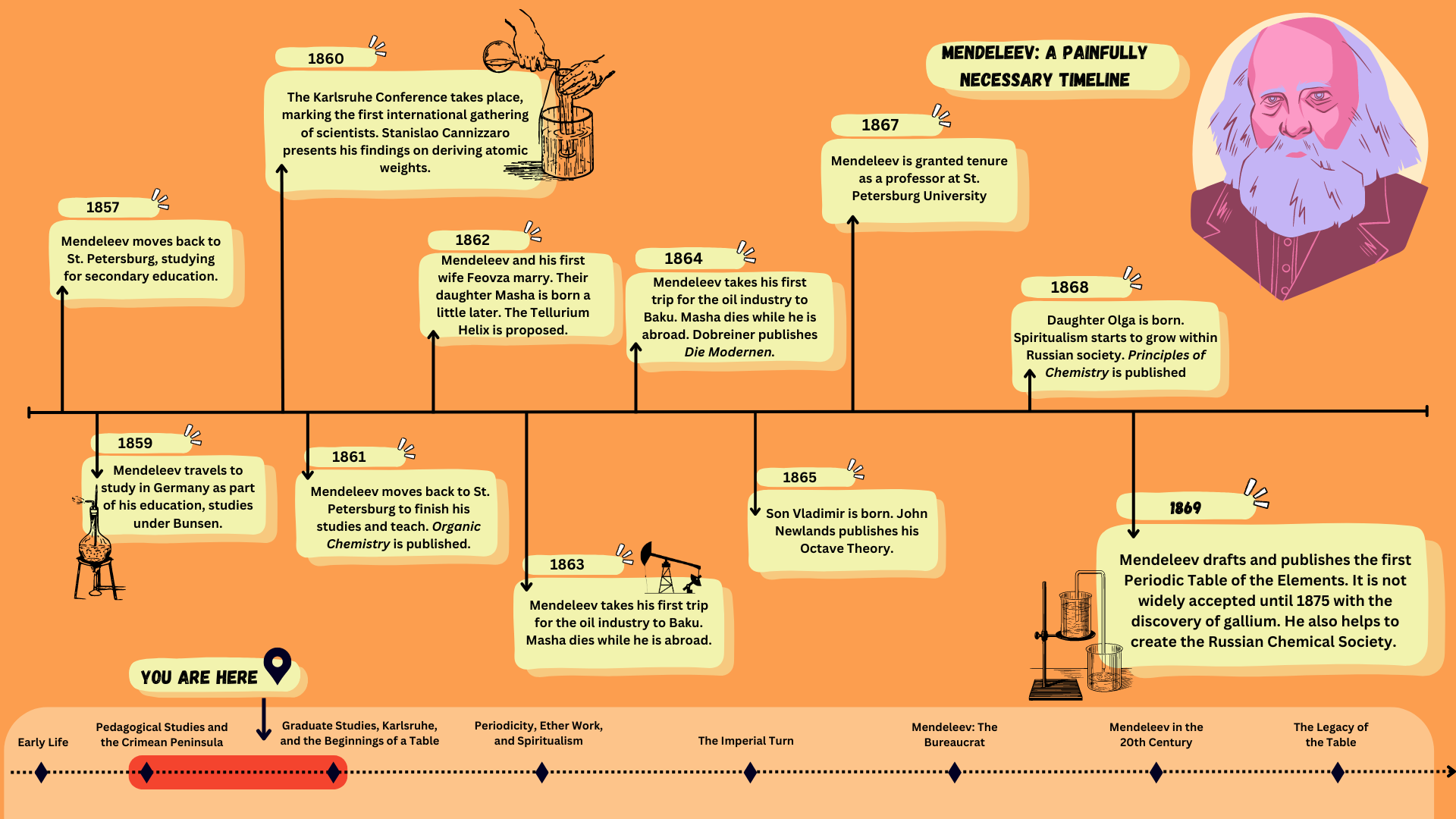

Scholars say that the next two years were some of the most important for Mendeleevs’ professional and personal development as he studied in Heidelberg under Robert Bunsen (yeah, that Robert Bunsen). Not only did it give him an opportunity to travel and experience life outside of the Russian Empire, but it also exposed him to a multitude of ideas that would eventually lead to the first periodic table.

Many of these ideas were presented at the Karlsruhe Conference in 1860, where renowned names in the physical sciences amassed to present and hear current findings in a variety of subjects. It was the first international congress of scientists and paved the way for organizations like the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) to form in the future.

It was here that Stanislao Cannizzaro expanded on Amadeo Avagadro’s hypotheses and presented his work on bridging atomic and molecular weights, paving the way for atomic mass units to be developed. This would slingshot fellow scientists into the question of, “how does it all fit together?”.

As scientists learned of new elements over the years, the question of how to present them grew evermore ugent. The consistent pattern in physical properties and behaviors of elements, or periodicity, was definitely on the mind of chemists before Karlsruhe. Indeed, Johann Wolfgang Dobreiner proposed his triad theory in 1829, just 5 years before Mendeleev would be born. Dobreiner’s triads would go relatively unnoticed until approximately 30 years later when the question begged to be asked again.

The upcoming decade would yield various proposals of chemical periodicity and organization, but none would stick until one day in St. Petersburg in 1869.

Bringing It Home

A certainly important aspect of Mendeleevs’ reality as a developing educator and chemist, bringing the Russian Empire up to date on scientific ventures was about as easy as it sounded. It would take too long for newly published work to be translated and brought to Russian classrooms and gymnasiums. By the time that those textbooks would reach desks, new material would have to be published and translated.

This demand for current scientific literature in the Russian Empire as well as in his own lecture halls, Mendeleev wrote for utility, he needed up-to-date textbooks in order to instruct his classes. But make no mistake, he was also working to make Russian scientists competitive.

He would write his first textbook, Organicheskaia Khimii (Organic Chemistry), in 1861. 500 pages of all he knew and learned.

1862 would yield a somewhat reluctant marriage to Feovza Nikitchna Leshcheva, him being somewhat coerced into marriage and the idea of “settling down”. Their first child, a daughter named Maria (referred to as Masha), was born either late that same year or in early 1863.

A quick side note to mention that 1863 led to a lifelong dedication to petroleum and industry within a developing Russian Empire. Invited to advise on petroleum production in Baku, now the capital of Azerbaijan. Mendeleev would be involved with the petroleum industry through his life, traveling on at least four separate trips to learn international industrial methods. He would seriously consider leaving the scientific world for a career in oil, but seemed to pull out of any deal at the last second.

Tragedy did not forget Mendeleev, as his daughter Masha would pass away while he was returning from his trip to Baku of that same year.

Not much is said or written about Masha herself, muchless Dmitri’s (or Feovza’s for that matter) emotional reaction to the loss of a child. As history sees it, life continued on.

After years of studying, Mendeleev successfully defended his doctorate in 1864 (the same year Meyer would publish Die Modernen) with his work on alcohols and water, and became a professor of chemistry in 1865 at St. Petersburg. Tenure at St. Petersburg was granted in 1866/1867. He and Feovza welcomed their son Vladimir in 1865, and their daughter Olga, in 1868.

Brief History of the Prequels

To get an idea of what information and ideals the scientific community was working with, we turn to France, Germany, and England.

The work of Alexandre-Emily de Beguyer de Chancountais, Lothar Meyer, and John Newlands helped pave the way towards a periodic table.

1862 would yield one proposal from Beguyer de Chancountais, who drafted what he called the, “telluric helix” or “screw”. A periodic attempt named for the fact that tellurium was placed at the center of the model, it did not gain notoriety until later in the decade.

The same year, Lothar Meyer would begin to write Die modernen Theorien der Chemie. Being the first among his contemporaries to group elements by valence number, as well as plotting atomic weight vs. atomic volume. Die modernen would be published in 1864, and Meyer would go on to expand on periodicity in late 1869.

Periodic curiosity was not restricted to the European continent. Englands’ John Newlands had crafted his, “Law of Octaves” and published it in 1865 to, again, not much critical acclaim. He drew heavily from Döbreiner’s triads by grouping elements into eight categories based off of mass number. However, it wasn’t until Mendeleev published his table that Newlands’, Chancoutais’, and Meyers’ work gained more traction.

For Mendeleev in the 1860’s, life went on. He had moved back to St. Petersburg at the beginning of 1861, and continued teaching and researching his doctoral thesis. Notably, he brought back a need to deliver all of the new developments learned at Karlsruhe to the Russian scientific view.

The Table, Dreamed and Drafted

The next few years for Mendeleev are perhaps the ones most mired in lore and legend. For the late 1860’s and early 1870’s helped cement the creation he is most known for and establish Russian identity within modern chemistry.

The world of chemistry was changing. And fast. Mendeleev was determined to keep the Russian Empire involved. Elements such as indium and cerium were being discovered seemingly daily thanks to newfangled technologies such as spectroscopy.

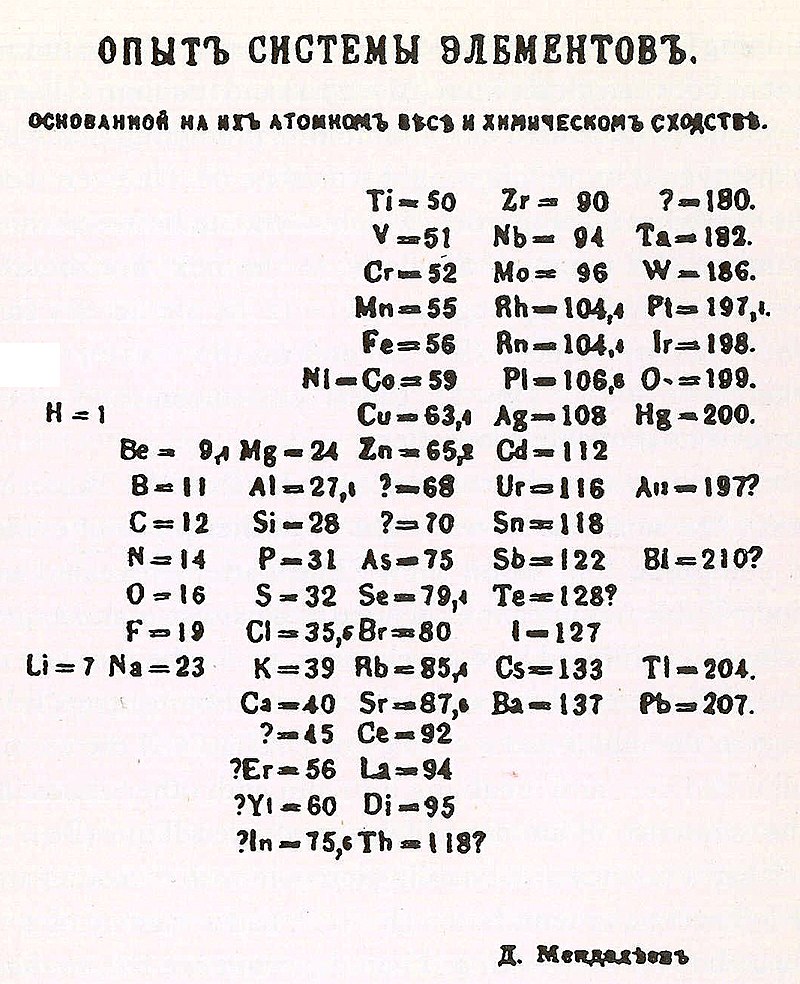

Whilst writing again, this time a set of textbooks for his inorganic chemistry lectures, Mendeleev felt the need for a way to organize and communicate the now 65 discovered elements more than ever. He started to draft The Principles of Chemistry (Oznovy khimii) in 1868, and realized he needed a diagram that could cohesively cram in all the elements and their properties while fitting into a University textbook.

Mendeleev reportedly kept a stash of cards, each with one of the known elements and its properties. By arranging by atomic weight (which had become an established part of atomic identity thanks to Cannizzaro and his presentation at Karlsruhe), Mendeleev puzzled them together basing his placements on what we now refer to as periodicity.

It is often quoted from Mendeleev himself (though I have yet to find exactly where he wrote this) that the Periodic Table came to him during a dream at his desk:

“In a dream I saw a table where all the elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper.”

Poetic, though if slightly doubtful, it makes for a good story. I don’t doubt that he may have dreamed of the cards, but it rings a little too glamorized for me. Either way, Mendeleev had cracked the periodic code.

Named for the repeating and predictable pattern of motion from a periodical function (such as sine or cosine functions), periodicity is recognized as a scientific law. It lies at an intersection of many underlying atomic properties such as atomic mass, atomic number, number of valence electrons, electronegativity, and volatility.

Named for the repeating and predictable pattern of motion from a periodical function (such as sine or cosine functions), periodicity is recognized as a scientific law. It lies at an intersection of many underlying atomic properties such as atomic mass, atomic number, number of valence electrons, electronegativity, and volatility.

In an article from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2019, Dr. Bassam Shakhashiri states that, “The periodic table is a great intellectual accomplishment because it brings together so many important components of the behavior of the elements.”

This is how the Periodic Table gained its name. Luckily, the underlying properties made it possible to create a table that was both flexible and predictable. By identifying and basing the table off of a fundamental aspect of atoms, Mendeleev was able to create an evergreen way of organizing the elements that could change and still uphold chemical law.

As Sam Lemonick wrote in an article for Chemical & Engineering News in 2019, “It’s been mutable from the beginning.”

With this, there were gaps in the table. For this, Mendeleev predicted three elements that would fit in those gaps. Granting them placeholder names: “ekaaluminum”, “ekasilicon”, and “ekaboron”, Mendeleev became a kind of chemical Cassandra, if you will.

The discoveries of the elements gallium (“ekaaluminum”) by de Boisbaudran in 1875, germanium (“ekasilicon”) by M.L.F. Nilson in 1879, and scandium (“ekaboron”) by Clemens Winkler in 1886 helped solidify that Mendeleevs’ table was a tool that could grow as chemistry grew. But it would be at least six years until the first confirmation.

Meanwhile in 1869, not everyone was convinced. Despite an overall grasp on periodicity, there were a few details that caused other chemists to hesitate on initial adoption, including the dubious positioning of tellurium and iodine. What was needed now was time and continued chemical research. And, hopefully, more elements to discover.

So let’s return to St. Petersburg in February of 1869. Mendeleev needs to write and publish his work – and fast. Meyer is right on his heels with an almost identical table of his own.

Mendeleev published first with The Relations Between the Properties and Atomic Weights of the Elements being printed just two weeks later; he was well on his way to cementing a legacy. Sorry Dobreiner, better luck next time. You can take a seat next to Leibniz over there.

1869 would also be the year that Mendeleev and other contemporaries founded the Russian Chemical Society, creating an organization to promote and support chemical research and development in the Russian Empire.

The enormity of what Mendeleev created in 1869 was not fully realized until halfway through the next decade. However, Mendeleev found himself puddling around with periodicity until very early into the 1870’s, when something bigger captured his attention.

As we head into the 1870’s we need to turn our view of Mendeleev from a scientific perspective to a social one, as Mendeleev was beginning to establish himself as part of St. Petersburgs’ social elite. The next ten years would yield massive social change for not just Mendeleev but the Russian Empire as a whole.

Before the Turn (1869 – 1880)

I cannot tell you how many drafts of this decade (rather, era, of Mendeleev’s life) that I have started and scratched. Is it because of immense societal change and renewed journalism in what was now a Great Reform Russian Empire, introducing new ways to connect across a large empire? Was it the total restructuring of society as citizens gained new rights and freedoms?

Maybe it was his failure to finally pin-down ether, a medium that wouldn’t start to be proven nonexistent until at least 1887, all the while spending the Technical Society’s prettiest penny? Or perhaps by the end to the decade, Mendeleev had gained a reputation as a stalwart anti-spiritualist (even though he was more aligned towards scientific study of these mediumistic experiences), who claimed that the powers of other-worldly knocks and convulsions were brought upon by the same ether that eluded Mendeleev in the lab?

One thing is quite clear and quite true.

The girlies are going to be fighting in St. Petersburg.

Ether and Pre-Commission.

Going back, the early 1870’s were focused on publishing the last text in his set The Principles of Chemistry, as well as continuing to fiddle with the Periodic Table – the organization of tellurium and iodine was really starting to chafe. However, his attention quickly diverted, back to organic chemistry, newfangled gas laws, and the entity known as “ether”.

Born out of Aristotle (I know, I know, the stoics again) aether was his explanation for the behavior of the sun, stars, and other celestial bodies. The famous “fifth element” or quintessence, aether had developed into an unseen yet perforative force that connected and influenced all. This idea rolled around alchemical and eventually chemical circles until it landed in the laps of 19th century chemists.

Ether at the time was seen as almost a vessel of causality, allowing unseen energies and forces such as light, heat, and gravity to act upon objects around them. Notably, it was thought that light would travel through what was referred to as, “luminiferous ether”, and was a medium that supposedly permeated all around, interspatially and interatomically.

Simultaneously, new gas laws, namely Gay-Loussac’s Law and Boyle-Marioette’s Law, which all have to deal with gas pressure, volume, temperature, and moles, showed inconsistencies. Mendeleev hypothesized that these inconsistencies arose from the presence of an unaccounted ether medium. By 1871 he was firmly in a gas studies venture that would prove unfruitful in time.

Additionally, his table was not widely accepted just yet. The noticeable gaps and overall unsureity made scientists hesitant to adopt it into practice just yet. The confirmation of his predicted “eka-elements” would prove scientific veracity, but this was still 1871. So for now it was a postulate, but periodicity was something still up in the air.

So, to the air he turned, and to ether. Mendeleev was trying to identify an even more fundamental law that underlied everything, whether it be on Earth or in space.

A short note about his other studies at this time, as Mendeleev is a multifaceted professional.

Mendeleev took one of many international trips to study oil and oil production in neighboring countries, notably a trip to Paris in 1873. This is another notch in his belt when it comes to petroleum and industry, and would contribute later in his career.

But back to that nutty little thing, ether. It wasn’t going to rest, and Mendeleev wasn’t going to either (ha, get it?). However, he was not the only one focused on ether.

Ether was making itself known within standard Russian society – Western Spiritualism had made itself known. Katie and Margaret Foxs’ fraudulent raps from 1848 New Jersey were now knocking upon early 1870’s St. Petersburg parlors.

Spiritualism

Spiritualism was a specific societal and cultural phenomenon that swept through at least the United States and Europe in the 18th into the 19th century.

It is important to note that the pracrtice of spiritualism and spiritual practices are still practiced and honored, and this is not a critique on those practices that many hold closely. This is also not a critique on mediums or any mediumship practices.

It can be argued that this era of American-born western spiritualism gives scientists and spiritualists and spiritual scientists grief because so much of it was sham work and discredits the values that both scientific and spiritual practices give us. So, there’s my white flag before I get into it.

What was important, it seems, to Mendeleev with the Spiritualist commission, was actually measuring what was going on. The temperature, gas pressure, etc. The thinking is if otherworldly appearances did make themselves known during seances, then that energy must be carried by ether, the very component Mendeleev was trying to pin down in his laboratory. Make no mistake, he was doubtful of these practices, but he wanted to measure what was going on. For it also threatened his ether studies, ones that were starting to fall apart by the mid 1870’s.

So what was actually happening? Well, spiritualism had grown from a backwater New Jersey instance, where it was further propelled by the American Civil War all the way across the Atlantic. Now it was fashionable for elites to hold seances, and the Russian nobility was struggling to stay relevant in Great Reforms Russia.

In May 1875, the Commission for the Investigation of Mediumistic Phenomena was established at the behest of Mendeleev. Two incorrect assumptions about this: 1) Mendeleev was not interested in persuading spiritualists on changing their minds, he wanted to make sure that he and the Russian Physical Society remained the legitimate interpreters of the natural world. 2) He was not interested as much in scientists that held to spiritualism, his studies were on the Russian nobility or the social elite and their role in spiritualism as perpetrators.

The Commission would prove to be frustrating, stunted, and halting. Mediums that fit the Commissions’ requirements were hard to find and often had to travel from overseas. Additionally, goodwill between skeptical and spiritual scientists started to break down by just the sixth session.

However, the ninth session of the Commission with two English brothers would confirm the duo as frauds and solidify Mendeleev’s name in St. Petersburg’s social sphere.

Quickly, on the night of November 20th, 1875, Mendeleev and others of the Commission sat with two brothers who had claimed they were mediums, but had failed to channel any otherworldly energy. The boys knew that if they couldn’t deliver, they were going to be sent back to England very soon. What they hadn’t anticipated was Mendeleev lighting a match about 45 minutes into the session, startling all attendants. A potentially tampered curtain, a bell on a table, all of it was put into question and sparked coals that were cooking underneath the feet of all on the commission.

Full collapse of the Commission would occur the next year, and Gordin sums it up to three causes:

- The inability of the commission to obtain what they considered qualified mediums, as well as the inability to stay on schedule to do logisticking (that’s a word) led to a procedural breakdown. Just, stuff wasn’t going the way it was supposed to.

- The imposition of experimental restrictions on the Commission – the Commission was being restricted by what they could measure and what was perceived as an imposition upon the medium. Therefore, there was an experimental breakdown, data wasn’t being gathered in the desirable fashion.

- With the arrival of Madame Claire in early 1876, a social barrier was constructed as well. Commission members had to take into account gentlemanly behavior now, and what would be appropriate with other men may not be with women.

Many like to take these events and paint Mendeleev as a favorite archetype – the stalwart, shaggy scientist opposing any and all notions of otherworldly happenings. That was probably an element, sure, but more than anything he was concerned about the role of scientists within social and cultural phenomena, angling for the University to be the leading authority on any natural phenomenon.

However, one can also note that Mendeleev well and truly made an ass of himself, creating too much ill will by unexpectedly lighting that match. People contain multitudes. This man, perhaps too much.

Anyway, spiritualism. A total commission report was drafted and published in the local paper The Voice. Mendeleev made a few public lectures about their findings, and published Materials for a Judgment on Spiritualism.

There would be a publishing battle between Mendeleev and the key commission member who brought Spiritualism to Russia, Aleksandr Aksakov. Going back and forth in the papers, publishing materials on their takes on commission events, Aksakov was furious at how Mendeleev had treated the mediums he had brought to Russia, and Mendeleev was frustrated that scientific phenomena needed to be spearheaded by scientific experts, not Russian nobility in their parlors.

The girlies are now fighting in St. Petersburg. It is the beginning of 1876.

But unfortunately, we have to go back to 1875. For there is a new kid on the chemical block.

Gallium – 1875 – a Short Reprieve

During Mendeleev’s attempts to isolate ether and the Spiritualism Commission, Paul Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran (we’re not laughing at the funny French name, he was a very serious science man) isolated the element gallium using a neat bit of spectroscopy. Named after his historical homeland, Gaul, gallium fit the bill of Mendeleev’s “Eka-aluminum”. Boisbaudran would solidify not only his name in chemical history, but Mendeleevs’ as well. His elemental prediction proved correct; he may be onto something here with the Law of Periodicity…

But! Two more “eka-elements” to go. This is only one data point.

1876 – Petroleum, War, Anna Popova (With a dash of Spiritualism)

Okay, we’re back in 1876! Gallium’s here. A final note about Spiritualism.

With a few lectures, the last one in April of 1876, and the publication of the accumulation of findings in Materials for a Judgment on Spiritualism, it seemed that the Spiritualism debate went to bed.

After the Commission, Mendeleev pivoted pretty quickly back to petroleum and industry. He traveled to Philadelphia in 1876 to gather more research on the American petroleum industry and attend the Worlds Fair held in Philadelphia. We’re not going to touch much on Mendeleev’s petroleum research itself, but more on how it shaped his internal and external views on Russia, and specifically, Russian industry. (Though the dude thought that oil came from rocks. I love this silly little guy. You can’t blame him but wow such good takes.)

Mendeleev believed, like many at the time, that industry was a way that Russia could propel itself onto the international stage. Indeed, this was a major dispute at the time for an empire varied in subjects. This would warrant a 10 page analysis of Russian socioeconomic systems in Pre-, during, and Post Great Reform Russia. And while that should be fully noted, that requires some time and more reading. So I ask for your patience and hope this meager offering is enough to tide us over until I can read.

We see some of how Mendeleev viewed the world during his piece, “Worldview”. Penned in 1877 but published in the 1890’s as part of his economic piece Cherished Thoughts. We see later on that Mendeleev leads his socioeconomic and political views with a heavy scientific lens.

1877 brought the Russo-Turkish War and all the pain and upheaval that invasion incurs. It must be noted that Russia was looking to reestablish itself after the Crimean conflict in the late 1850’s. There is much to be written about this subject, but we require only a tidbit. Just note that the Russian Empire was once again at war, and was spending the money to be there.

Industry and petroleum, conflict and war, the Russian Empire was working to establish itself as a dominant voice. The thing is, despite his desire to establish Russia with scientific experts, Mendeleev was distracted. He was crushing hard. He’s got it bad.

Anna Ivanova Popova was around 17 to 19 years of age, with reports of her birth ranging from 1858 to 1860. An art student, she had secured lodging in St. Petersburg with none other than Mendeleev’s older sister, Ekaterina Kasputina. This was where the two would meet.

Mendeleev would quickly become infatuated with the young student, and supposedly the two quickly earned the nicknames of, “Faust and Margarita”. He began to organize social meetings of local elites and artists on Wednesday nights, just to have an excuse to talk with her and help boost her career.

Not wanting to damage his reputation (insert reaction here), Mendeleev attempted to distance himself from Popova. It was all in vain; he first proposed in 1879 (for some reason she said no). Popova’s father didn’t like that, and traveled to St. Petersburg to chew out Mendeleev. He then sent Anna to Italy in December of 1880.

We now have to put a pin in that again, and head back a month before to November 1880.

Where we are so far:

Leave a comment